Design patterns for AI agents

Everyone's building AI agents. Fewer people are thinking carefully about *how* to architect them. Should you put all your tools in a single monolithic agent? Split them across specialized sub-agents? If so, how should those sub-agents communicate?

These are questions I kept running into at work, and I found the existing discourse unsatisfying – lots of hand-waving, not much rigor. So I did what any self-respecting engineer does on a weekend: I built a model. This post walks through that model, the design patterns it compares, and what the results suggest about when to use which architecture.

Fair warning: this is explicitly a rough, "back of the envelope" exercise. The goal isn't to produce a definitive answer, but to build intuition about the tradeoffs involved.

What is an AI agent?

Before modeling agents, it helps to agree on what we're talking about. The major AI labs have offered their own definitions:

Anthropic's take:

Agents can handle sophisticated tasks, but their implementation is often straightforward. They are typically just LLMs using tools based on environmental feedback in a loop. It is therefore crucial to design toolsets and their documentation clearly and thoughtfully.

OpenAI's take:

Agents are systems that independently accomplish tasks on your behalf.

LangGraph's take:

An agent consists of three components: a large language model (LLM), a set of tools it can use, and a prompt that provides instructions.

These are all reasonable, but I think they miss some nuance. Here's my (humble) attempt at a more complete definition:

An AI agent is a computer system that autonomously acts on behalf of a human client to maximize its client's utility over time. It perceives its environment, reasons about the best actions, executes them at the right times, and communicates with both its client and its surroundings. To function effectively, it must remember and recall information about its environment and objectives.

The key additions are autonomy, utility maximization, and memory – the last of which is often overlooked but critical for any agent that operates over more than a single request-response cycle. (I've written more about this in a previous post.)

Do you need an AI agent?

Before reaching for the agent hammer, there are two prerequisite questions worth asking honestly.

Do you need LLMs at all?

Probably not, if:

- Your problem can be solved deterministically with low effort (e.g. counting the number of "r"s in "strawberry")

- You have a very strict latency, cost, or compute budget (e.g. ranking ads in the request path at <50ms)

- Your input space is fairly small (e.g. digit recognition -- the MNIST problem)

- Your output space is fairly small (e.g. binary classification: is this an apple or not?)

- There are existing ML models that already solve the problem well (e.g. Whisper for speech-to-text; sentence transformers for semantic matching)

Maybe, if:

- None of the above apply

- Your input space is very large: you need to process natural language with highly variable inputs, or work with large unstructured inputs (thousands of words or more), or handle multimodal inputs (PDFs + user messages)

- Your output space is generative -- very large and non-deterministic (e.g. responses to users, possible actions to be taken)

- You need reasoning to be exposed

Do you need agents specifically?

Probably not, if:

- You can design a structured workflow (e.g. traditional RAG, or summarization pipelines)

- You have very strict latency or cost requirements

Yes, if:

- You don't know how many steps something might take

- You have a very large tool set (difficult or impossible to identify all possible workflows a priori)

- You want to take a leap of faith into this brave new world

There's an implicit tradeoff here between short-term and long-term pain. Structured workflows require more upfront design effort but are predictable and controllable. Agents require less upfront work but introduce nondeterminism, debugging complexity, and ongoing operational cost. The right choice depends on your problem's complexity and your tolerance for uncertainty.

Common design patterns for agentic AI systems

At their core, multi-agent systems are really about one question: how should tools be distributed (and replicated) across agents? The four patterns I compare in this analysis are:

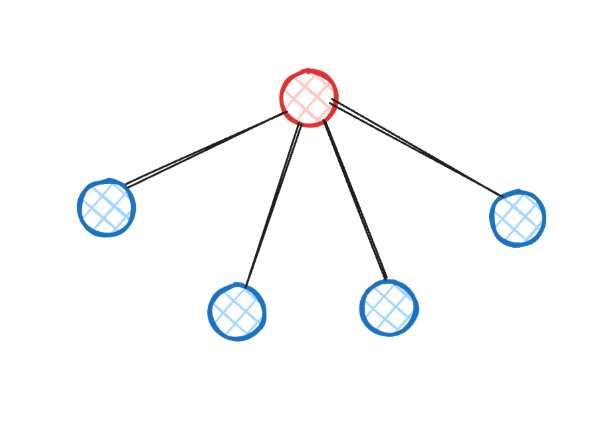

Single Agent (Monolith)

One agent holds all available tools. Simple. No coordination overhead. This is what most people start with, and for good reason.

Hub & Spoke

A supervisor agent holds the most commonly used tools, plus knowledge of multiple "sub-agents" that each own a subset of the remaining tools. Sub-agents can't talk to each other – all communication goes through the hub.

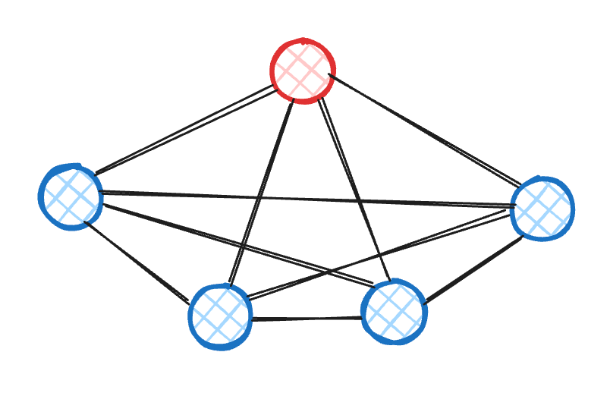

Hub & Mesh

Same as hub & spoke, but sub-agents *can* communicate directly with each other. The hub still handles the most common tools and serves as the entry point.

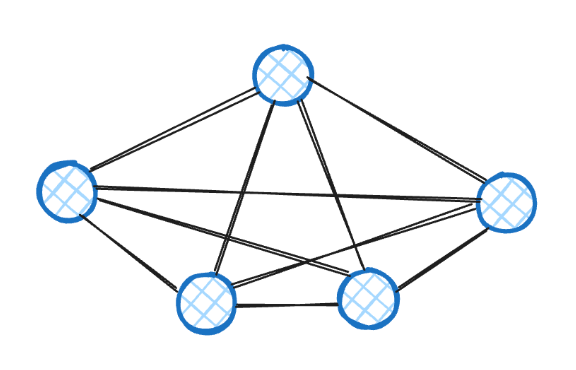

Clique

Completely decentralized. Each agent has a subset of tools, and every agent is aware of every other agent. There is no designated supervisor. Each agent has roughly the same "tool demand mass" (which may or may not translate to the same number of tools, depending on how skewed tool usage is).

4. Modeling setup

Caveat: This is a very rough weekend side project. Treat results as directional, not definitive.

What we're optimizing

We care about three things, in rough order of importance:

1. Token count – this directly maps to cost and latency, and is possibly proportional to accuracy (more tokens = higher chance of erroneous output). Not all tokens are equal: output tokens are slower and more expensive than input tokens.

2. Latency – since there is likely a fixed minimum latency per turn, the number of turns (and the distribution of input/output tokens over turns) matters. This reflects the end-user experience more directly.

- Cost ($) – typically a hard budget constraint.

Modeling tool demand

Each user request requires a random number of tool invocations. We assume this follows a Poisson distribution, i.e. the mean number of tools required per request is $\lambda$:

$$K \sim \text{Poisson}(\lambda)$$ Let there be $N$ tools. Tool usage can be distributed either uniformly or via a Zipf (power law) distribution with parameter $\alpha_{pl}$. Tool $r$ is used with probability: $$w_r = \frac{r^{-\alpha_{pl}}}{\sum_{j=1}^{N} j^{-\alpha_{pl}}}$$ At $\alpha_{pl} = 0$, tools are equally likely to be used (uniform distribution). As $\alpha_{pl} \to 1$, the distribution becomes "head-heavy" -- the most popular tool is roughly $X$ times as likely to be used as the $X$-th most popular tool. This mirrors many real-world distributions (think letter frequencies in English, or API endpoint popularity).

Modeling input token count

For agent $i$ with scope $|S_i|$ tools, the number of input tokens per call $L_i$ can be modeled as: $$L_i = L_0 + \alpha \cdot |S_i|$$ Where $\alpha$ is the number of tokens per tool definition (schema, parameters, etc.) and $L_0$ is the base system prompt length.

For the hub models (hub & spoke, hub & mesh), we assign tools to the hub based on a **demand mass** model: sort tools by likelihood of use (their "mass"), and assign the most-used tools to the hub. The hub's mass $\Phi$ satisfies $0 < \Phi < 1$, and spoke $j$ (of $m$) has mass $\phi_j$ such that: $$\Phi + \sum_{j=1}^{m} \phi_j = 1$$

Modeling number of turns

The expected number of turns (LLM calls) per user request is: $$\mathbb{E}[\text{turns}] = \underbrace{(1 + \mathbb{E}[K])}_{\text{baseline}} + \underbrace{h \cdot \mathbb{E}[(K-1)_+] \cdot B(\text{design})}_{\text{hand-off turns}} + \underbrace{e \cdot \mathbb{E}[K] \cdot \bar{\varepsilon}}_{\text{error retries}}$$ Where $B(\text{design})$ is the boundary crossing rate (the probability that consecutive tool calls land on different agents), and $\bar{\varepsilon}$ is the average tool mischoice probability.

Strong assumption: one tool per turn (no parallelization). This assumes tool calls are highly interdependent, which is obviously not always true. A relaxation for future work.

Modeling latency

$$\mathbb{E}[\text{latency}] = t_{\text{in}} \cdot \mathbb{E}[\text{turns}] + \frac{\mathbb{E}[\text{output tokens}]}{\text{throughput}} + t_{\text{tool}} \cdot \mathbb{E}[K]$$ Where $t_{\text{in}}$ is the fixed per-turn input processing time, and we assume $t_{\text{tool}} = 0$ (ignoring tool execution time -- this might haunt us if tool choice errors are significant). Throughput figures are based on average values for GPT-4.1 from OpenRouter.

Modeling tool overlap and choice error

This is where things get interesting. We model a penalty for having more tools in scope, based on a higher likelihood of the agent choosing the wrong tool ("mischoice"), driven in part by tool definitions having semantic overlap with each other.

Tool overlap:

$$\omega = \omega_0 + \zeta \cdot \ln(N) + \eta \cdot \alpha_{pl}$$

Mischoice probability for agent $i$:

$$\varepsilon_i = \varepsilon_0 + \gamma \cdot \omega + \delta \cdot |S_i|$$ Where $\omega_0$ is the base overlap, $\zeta$ captures how overlap increases with more tools, $\eta$ captures how overlap increases with skewness, $\varepsilon_0$ is the base mischoice rate, $\gamma$ is the sensitivity to overlap, and $\delta$ is the sensitivity to scope size.

| Parameter | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| $q_{\text{choose}}$ | 50 | Input tokens per chosen tool |

| $o_{\text{final}}$ | 100 | Output tokens per tool call |

| $L_0$ | 1,000 | Base system prompt tokens |

| $\alpha$ | 100 | Tokens per tool in scope |

| $\Phi$ | 0.3 | Demand mass of hub (supervisor) |

| $\alpha_{pl}$ | 1.0 | Zipf exponent (fairly head-heavy) |

| $\omega_0, \zeta, \eta$ | 0.05 each | Overlap parameters |

| $\varepsilon_0$ | 0.05 | Base mischoice rate |

| $\gamma$ | 0.10 | Mischoice sensitivity to overlap |

| $\delta$ | 0.02 | Mischoice sensitivity to scope |

| Input cost | $2 / 1M tokens | GPT-4.1 pricing (OpenRouter) |

| Output cost | $8 / 1M tokens | GPT-4.1 pricing (OpenRouter) |

| TTFT | 0.72s | Time to first token (1K input) |

| Output throughput | 73 tok/s | Output generation speed |

Scenarios

| Simple | Moderate | Moderate (many cooks) | Complex | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| $N$ (tools) | 5 | 50 | 50 | 500 |

| $\lambda$ (mean steps) | 2 | 5 | 5 | 10 |

| Non-supervisor agents | 2 | 5 | 25 | 25 |

| Tools per non-supvr agent | ~2 | ~7 | ~2 | ~15 |

Initial observations

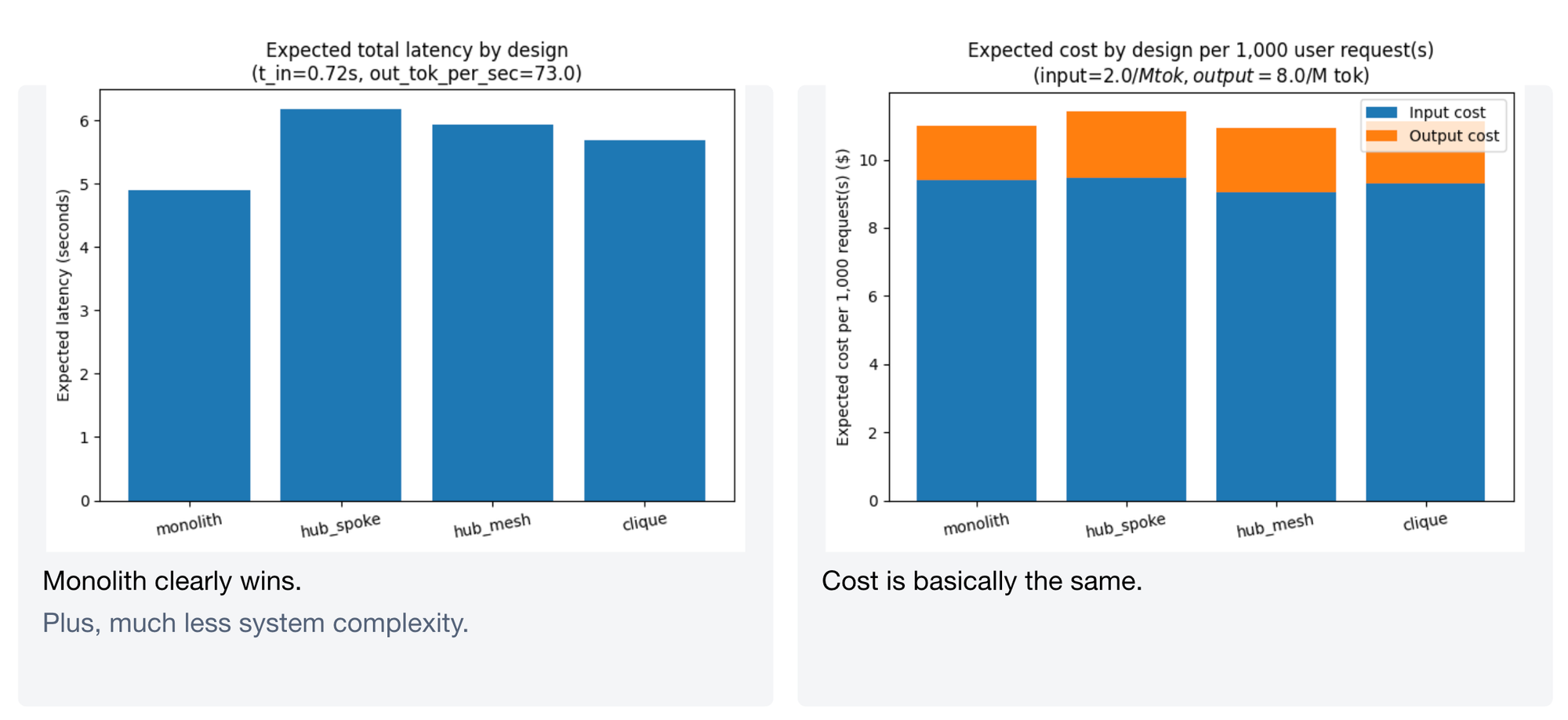

Simple scenario

Monolith wins clearly – and it isn't close. Lower latency, comparable cost, and much less system complexity. If your problem is simple, there is no reason to introduce multi-agent coordination overhead.

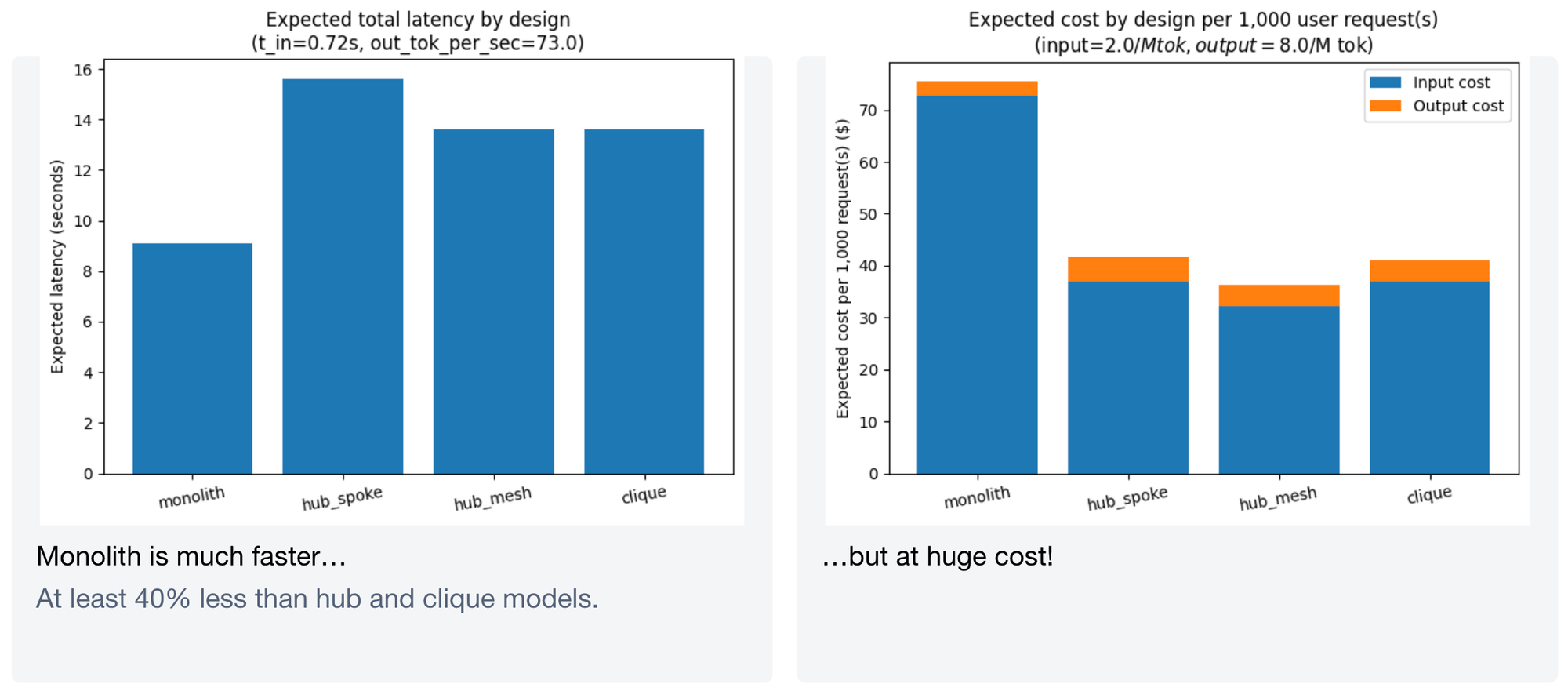

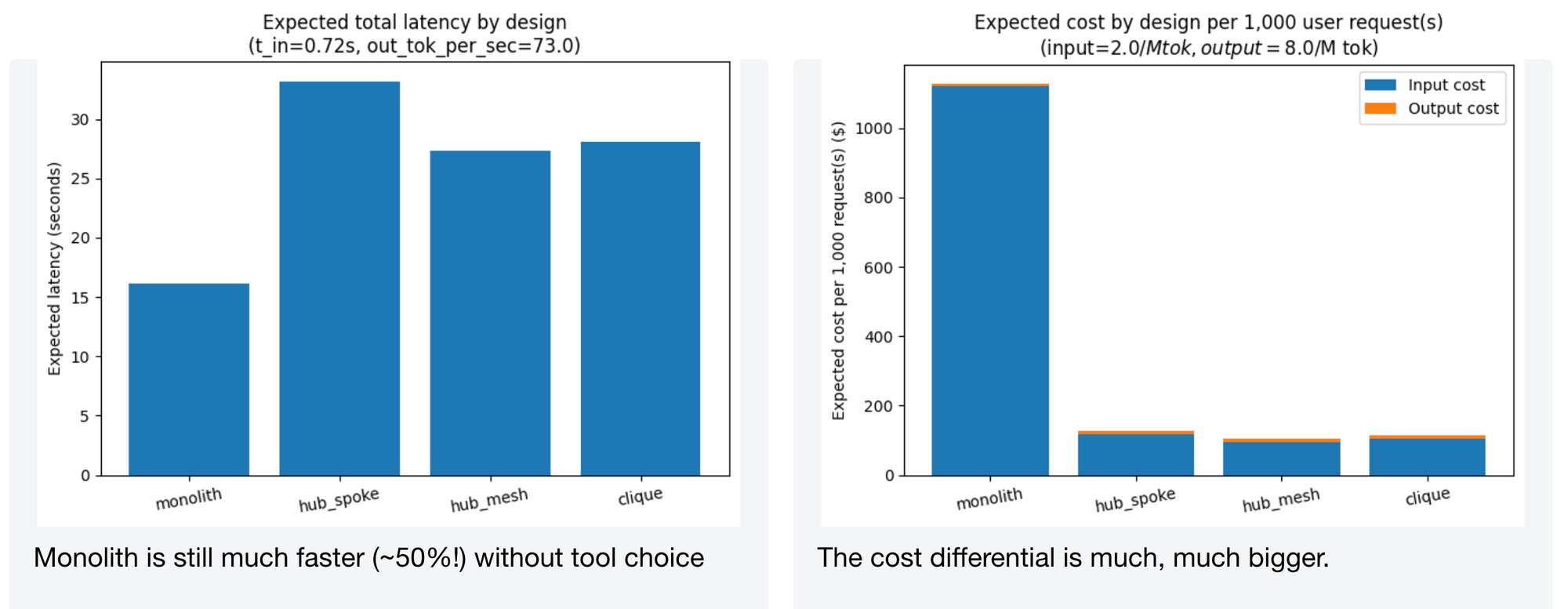

Moderate scenario without tool choice error

Monolith is much faster – at least 40% less latency than hub and clique models. But it comes at a significant cost premium. This is the naive case: if your tools are sufficiently distinct that the model never picks the wrong one, monolith's speed advantage from avoiding inter-agent hand-offs dominates.

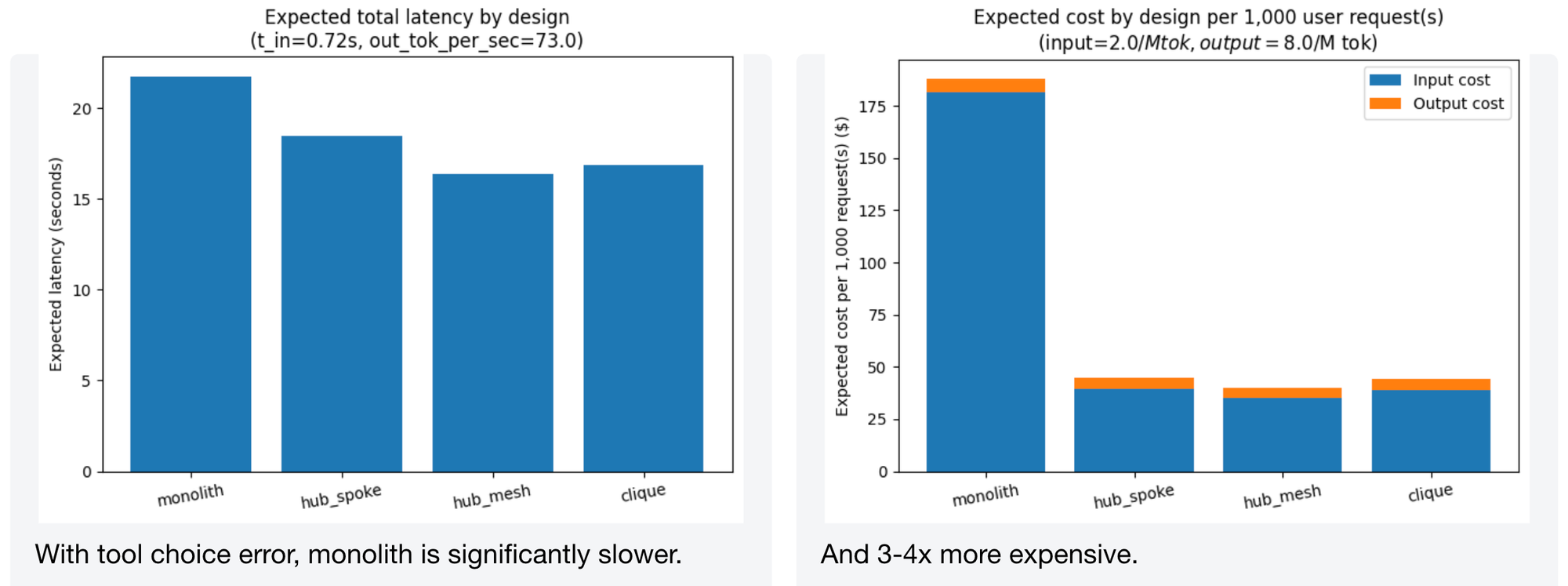

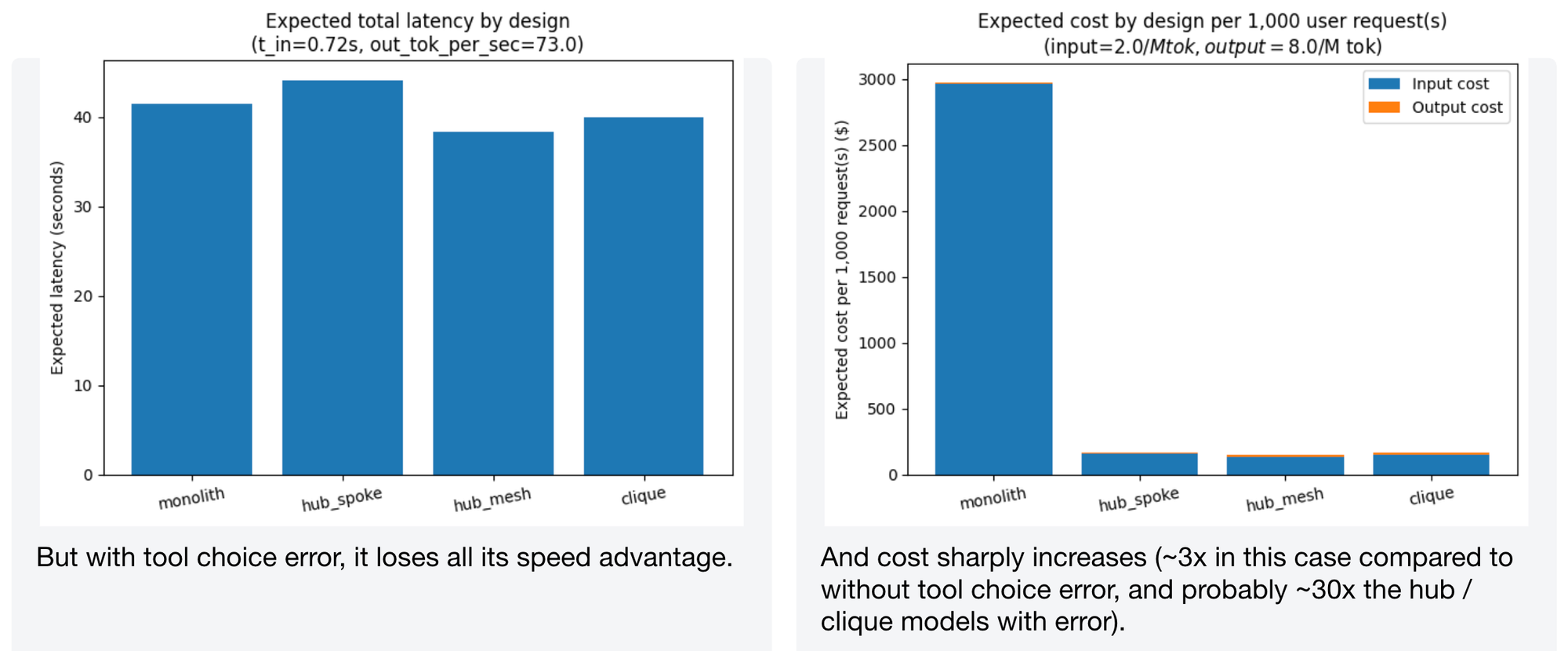

Moderate scenario with tool choice error

This is where the story changes. With tool choice error modeled, the monolith becomes significantly slower (all those retries with a massive tool set add up) and 3-4x more expensive. The multi-agent architectures limit each agent's scope, which reduces mischoice probability per turn.

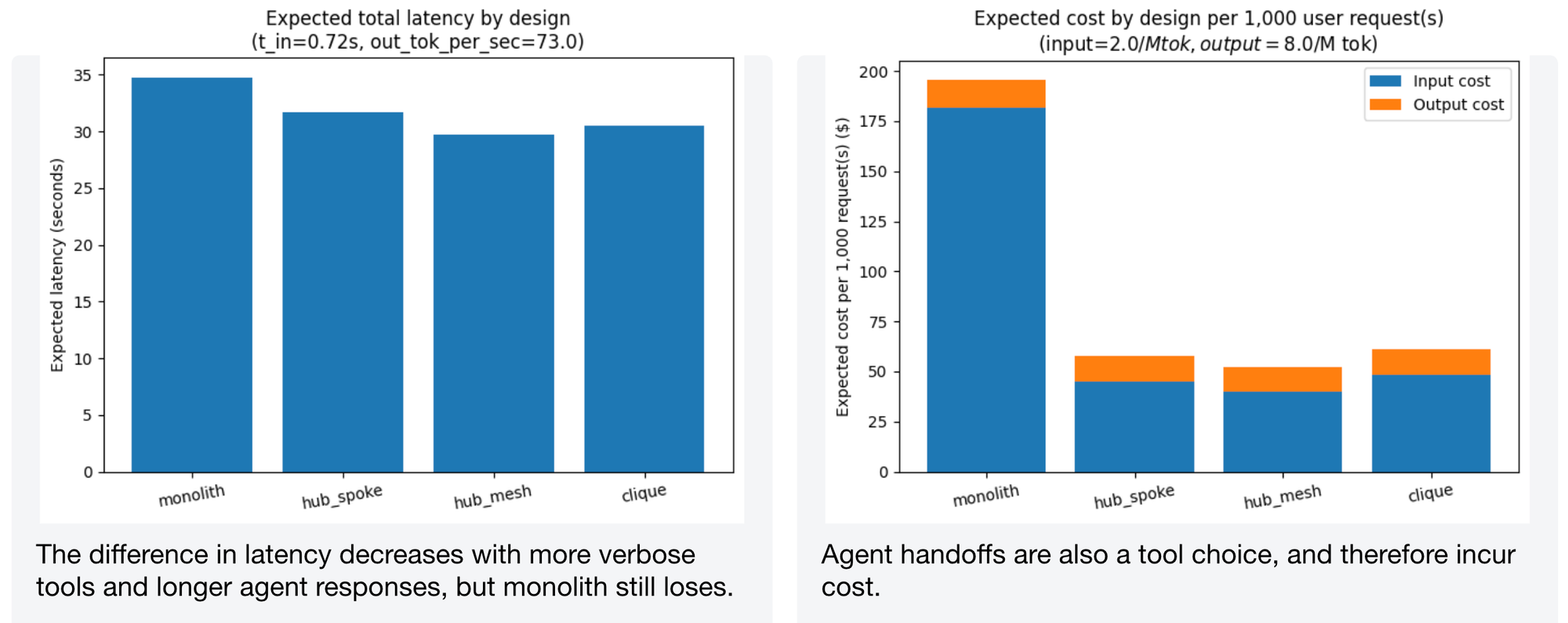

When we increase tool verbosity and response length, the latency gap narrows – but monolith still loses. And agent hand-offs themselves are also a form of "tool choice" that incurs cost, which the model accounts for.

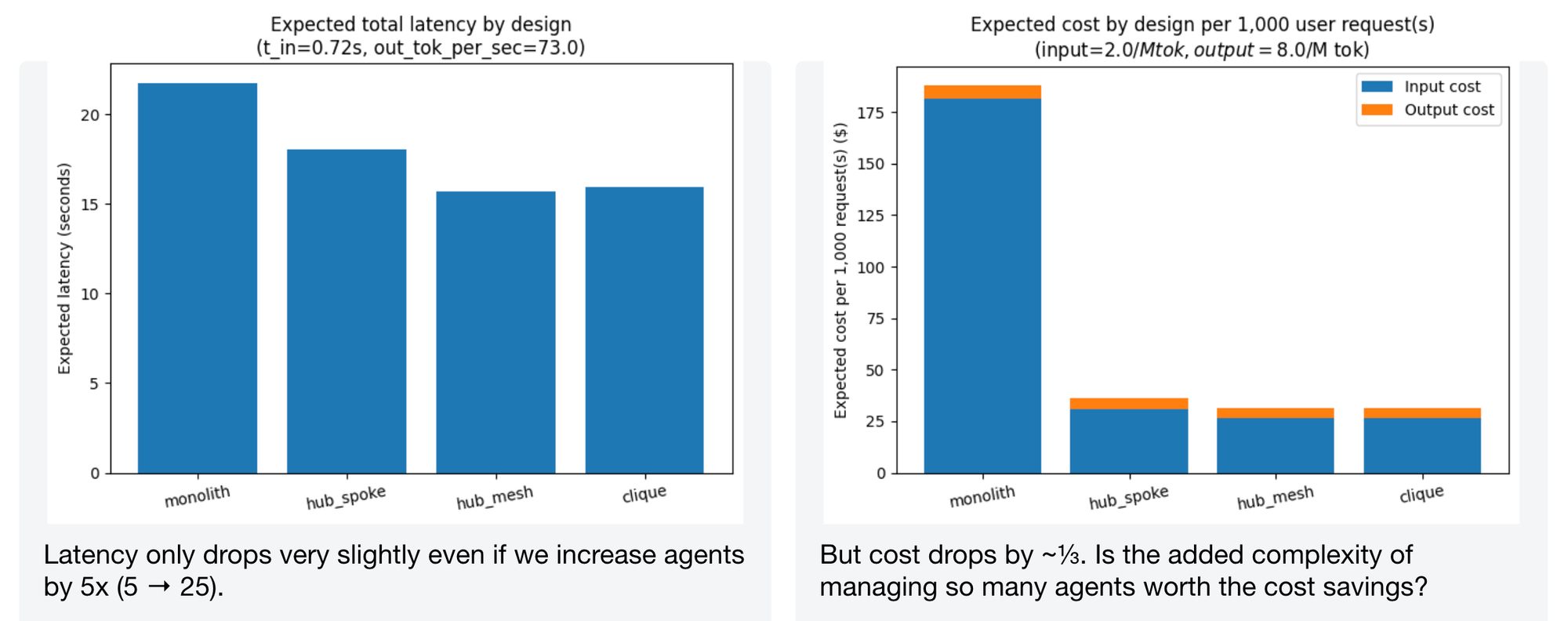

Many cooks in the kitchen

What happens if we increase from 5 agents to 25 while keeping the problem the same size (50 tools, $\lambda = 5$)? Latency drops only slightly, but cost drops by roughly a third. Whether the added complexity of managing 25 agents is worth that cost saving is a judgment call that depends on your operational maturity.

Complex scenario

Without tool choice error, monolith is still much faster (~50%), but the cost differential becomes enormous – we're talking orders-of-magnitude differences.

With tool choice error, monolith loses all its speed advantage. Cost balloons to roughly 3x compared to without error, and probably ~30x the hub/clique models. This is the regime where multi-agent designs aren't just nice-to-have – they're necessary.

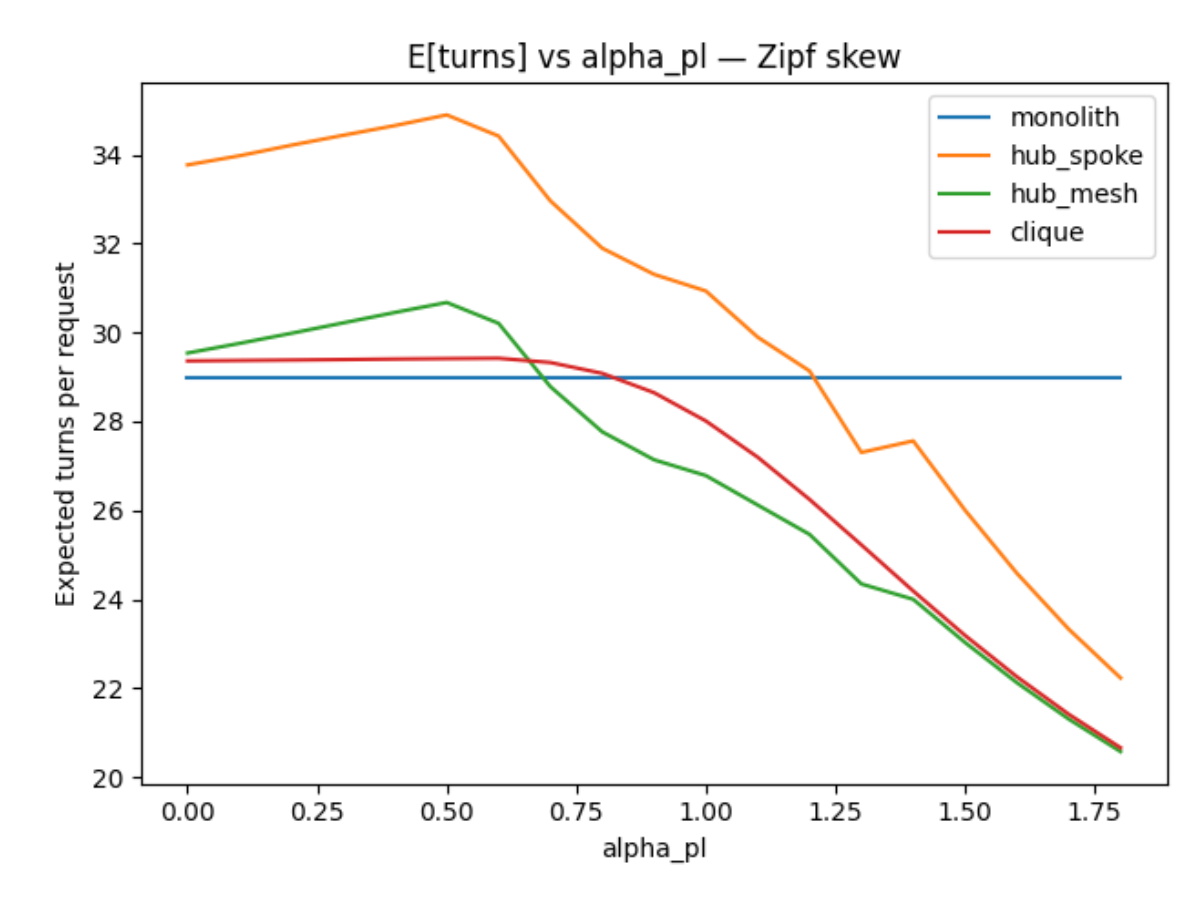

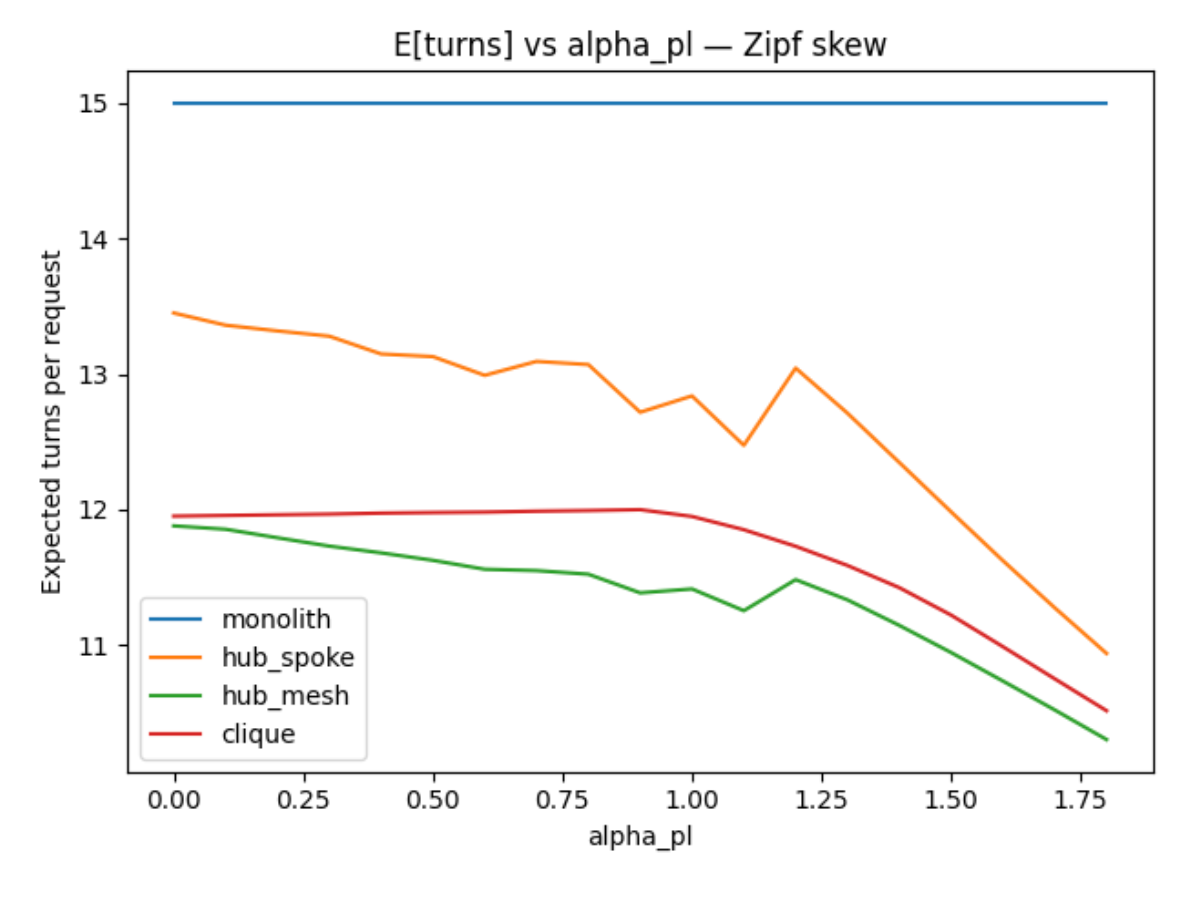

Effect of tool distribution skewness

As tool usage becomes more skewed (higher $\alpha_{pl}$), the monolith's advantage in number of turns erodes. Decentralization starts paying off because the hub models can keep the "hot" tools local while distributing the long tail.

In the moderate scenario with tool choice error, the monolith consistently takes more turns while hub/clique models trend better as the problem gets easier. In most cases, hub & mesh appears to work somewhat better than hub & spoke.

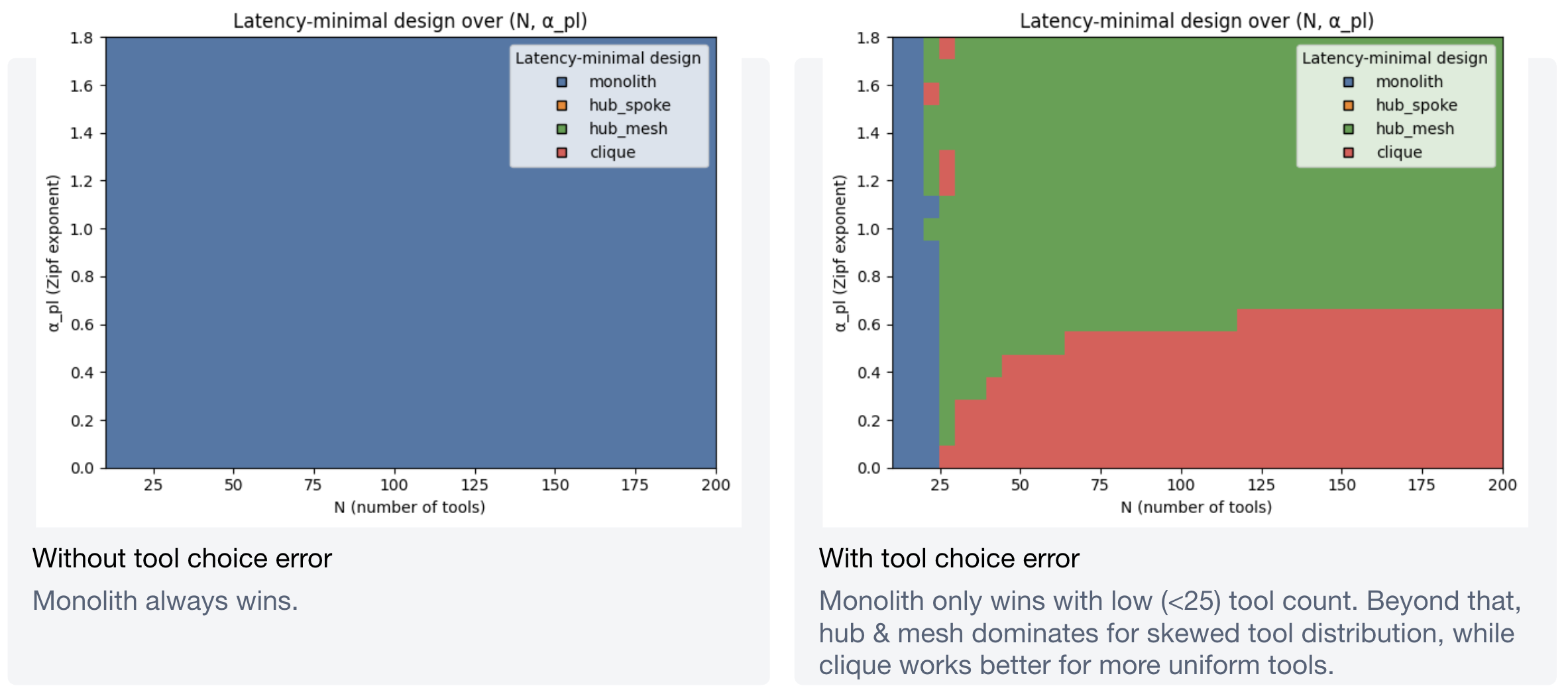

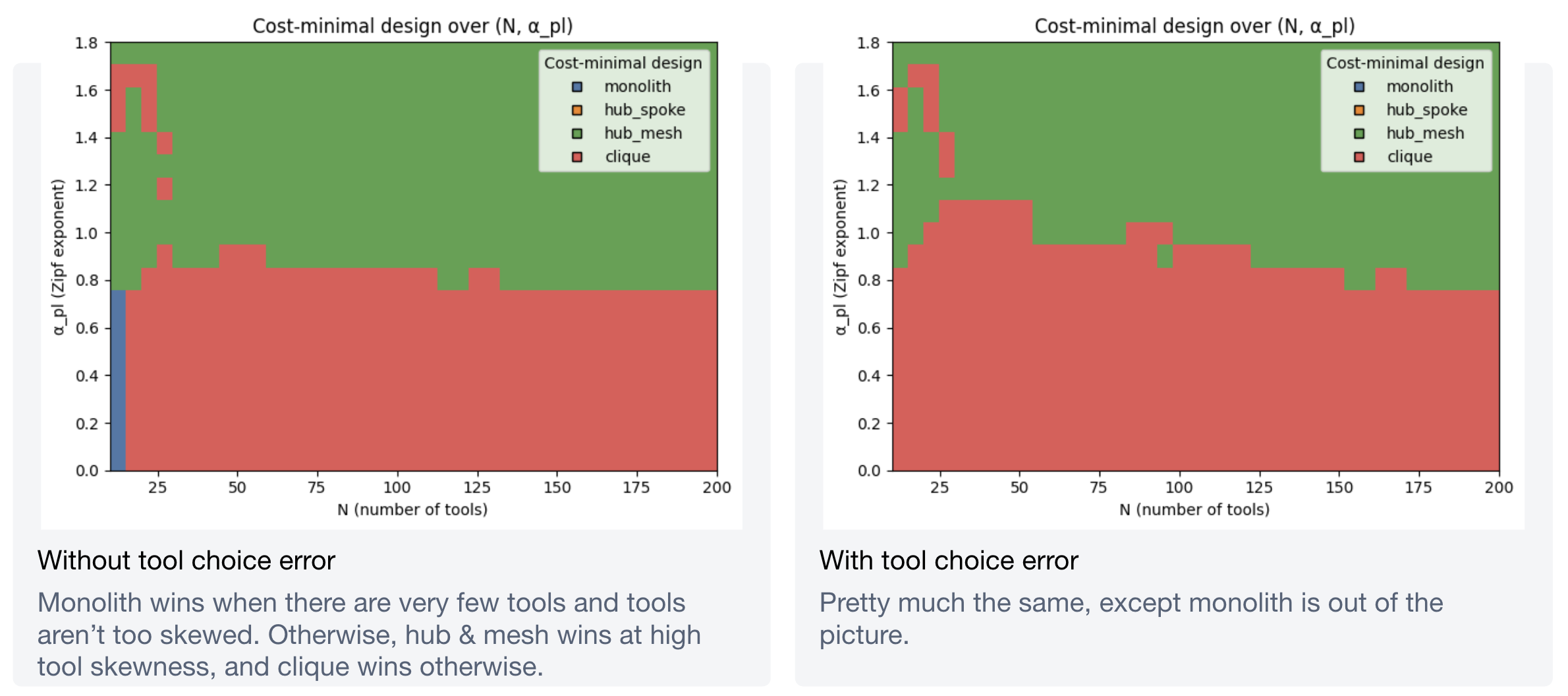

Optimizing over tool count and skewness

The heatmaps tell a clean story. For latency:

For cost:

Overall findings

-

In simple scenarios, use a monolith. Much lower complexity for similar latency and cost. Don't over-engineer.

-

Hub & mesh >> hub & spoke. In essentially every scenario, allowing sub-agents to talk directly to each other (rather than routing everything through the supervisor) is faster and cheaper. Intuitively, this makes sense: mapping a large tool space into a relatively small number of agents is cheap, and hub & mesh requires one hop between spokes where hub & spoke requires two.

-

For moderate complexity, monolith might work if tools are very distinct. It offers lower latency at higher cost. But once tool overlap and choice errors enter the picture, monolith loses its latency advantage -- hub & mesh becomes both faster and cheaper.

-

Hub & mesh vs. clique depends on tool distribution skewness. Hub & mesh is almost always faster and cheaper when tool usage is skewed (which is common in practice -- think Zipf's law). Clique works better when tools are more uniformly distributed. This makes intuitive sense: hub & mesh benefits from having a fixed entry point that handles the most common requests.

-

More agents = faster and cheaper (in moderate and complex scenarios with tool choice error). More agents mean a more partitioned graph, which translates to lower scope per agent, less overlap, and lower error probability.

-

Clique could benefit from non-LLM optimizations -- for example, semantically routing to the best initial agent based on the user's request, rather than randomly or round-robin.

tl;dr: Always start with a monolith. Then move to hub & mesh or clique based on your tool distribution's skewness. Starting with a monolith also gives you the empirical data (tool usage counts, skewness, error rates) you need to make an informed decision about when and how to decompose.

Caveats and future work

This model is explicitly rough. Some known limitations and possible extensions:

- No empirical validation yet. These are analytical results from a model with many assumptions. They need to be tested against real workloads.

- Results may not generalize. Need to check sensitivity to model parameters (more succinct instructions, cheaper hand-offs, different model cost profiles, etc.).

- Token caching could significantly change the results, especially for monolith designs where the same large context is sent repeatedly.

- Stochasticity is missing. The model uses expected values; real-world systems have variance. Some calls time out, some fail, some take much longer than average.

- The "one tool per turn" assumption is strong. In practice, agents often invoke multiple tools in parallel within a single iteration (e.g. parallel search queries). Relaxing this would likely narrow the gap between monolith and multi-agent designs.

- The code needs to be published along with a more formal write-up. Ideally, I'd like to build a simulation tool where actual prompts and tool definitions can be tested to find the ideal design -- across different models, too.

Member discussion