Detecting bot traffic

How can we differentiate bot from human traffic? What are some typical features?

How to identify (bad) bot traffic?

It is always possible to detect bad bot traffic, as long as there is sufficient volume.

Aggregating traffic via dimensions

Grouping traffic together based on certain attributes (or dimensions) allows us to abstract the traffic so that we can measure and compute certain properties for each group, and compare across groups.

We will first discuss some frequently used dimensions and then move on to common traits for bots and for legitimate human traffic.

These are some common dimensions that we can derive purely from web traffic logs:

IP address

Use this with caution. While devices generally maintain the same IP address over the course of a short session or series of transactions, this is not necessarily the case over a longer time period. And each IP address may map to one device or thousands of devices -- for example, a corporate network may have thousands of (very similar!) devices behind a single IP address. Even a single mobile IP address, such as one belonging to AT&T's mobile network, may simultaneously represent multiple users. Also, watch out for IPv6 addresses: with the huge address space, attackers can use a huge amount of IPv6 addresses in short order. As an example, a persistent attacker on a popular social network sent in hundreds of millions of requests over several days -- using a unique IPv6 address for every 1-2 requests!

It is tempting to block obviously bad traffic from specific IP addresses, but this is a cat-and-mouse game. IP addresses are cheap, and it is trivial for attackers to use new IP addresses. There is also a very real risk of accidentally blocking legitimate users sharing the same IP address as an attacker. This can be sidestepped somewhat by letting IP address blocks expire, but figuring out the optimal expiration timestamp is also challenging.

ASN

This is the next step up from IP address, and it is useful because the number of ASNs is orders of magnitude smaller than the number of IP addresses. It is also useful because we can start to categorize ASNs into various types: residential, mobile, and cloud/hosting. We can also compute the reputation of each ASN in several ways (or by using an external data provider like Maxmind, Neustar, or IPQS). Note that server logs do not typically contain ASN, and they have to be enriched with this information based on the IP address.

Country

With the ASN, one can derive the ASN's country. This is useful for identifying traffic from unexpected countries – for example, a website that primarily serves Latin America should not see too much traffic from, say, Iran. Take note, however, that this dimension is useless for websites that implement geoblocking (i.e. allowing access by users only from certain countries).

User Agent (UA)

User agent strings hold a lot of useful information, but people often ignore them because it takes a lot to cut through the noise to find any useful signal. If you are not familiar with user agents, here is a hilarious (and very apt!) history, and here is a more serious write-up. Note though that these articles are over a decade old, and have not captured many of the latest developments surrounding user agent strings, such as user-agent reduction in Chrome.

Most web traffic contains a UA header, but the most basic automated requests, such as those sent via CURL or Python Requests, often do not declare such a header. This makes them stand out from the crowd.

In the last five to ten years, UA strings have arguably become less useful as a dimension. As more browsers automatically update to the latest version, most of the browsers in any given traffic sample would be on the latest browser version. However, this is also advantageous in another sense: older browser versions, which are often employed by bots, now stand out a lot more.

Cookie values

Cookies are classified as either first-party or third-party.

First-party cookies are set by the website itself and can only be read by webpages on the same subdomain. Such cookies often contain some unique identifier that is set by the server, and they are therefore highly collision-proof. The fact that first-party cookies are automatically attached by the browser as part of every request enables such cookies to be tracked very reliably. This is especially true of GET requests, which do not contain any application payload or request body.

On the other hand, third-party cookies can be read across domains. They are frequently used for advertising tracking and are rather unreliable from a security standpoint. Over time, they have developed a relatively bad reputation and are increasingly blocked by browsers (for example, see Firefox's Enhanced Tracking Protection and Safari's Intelligent Tracking Prevention).

HTTP Header fingerprints

A great deal of research has been done on header fingerprinting. Such "fingerprints" are constructed based on certain properties of the HTTP header.

For instance, the order of headers in an HTTP request matters. Each browser typically sends request headers in a certain sequence, and we can exploit that to cluster traffic by major browser/operating system settings.

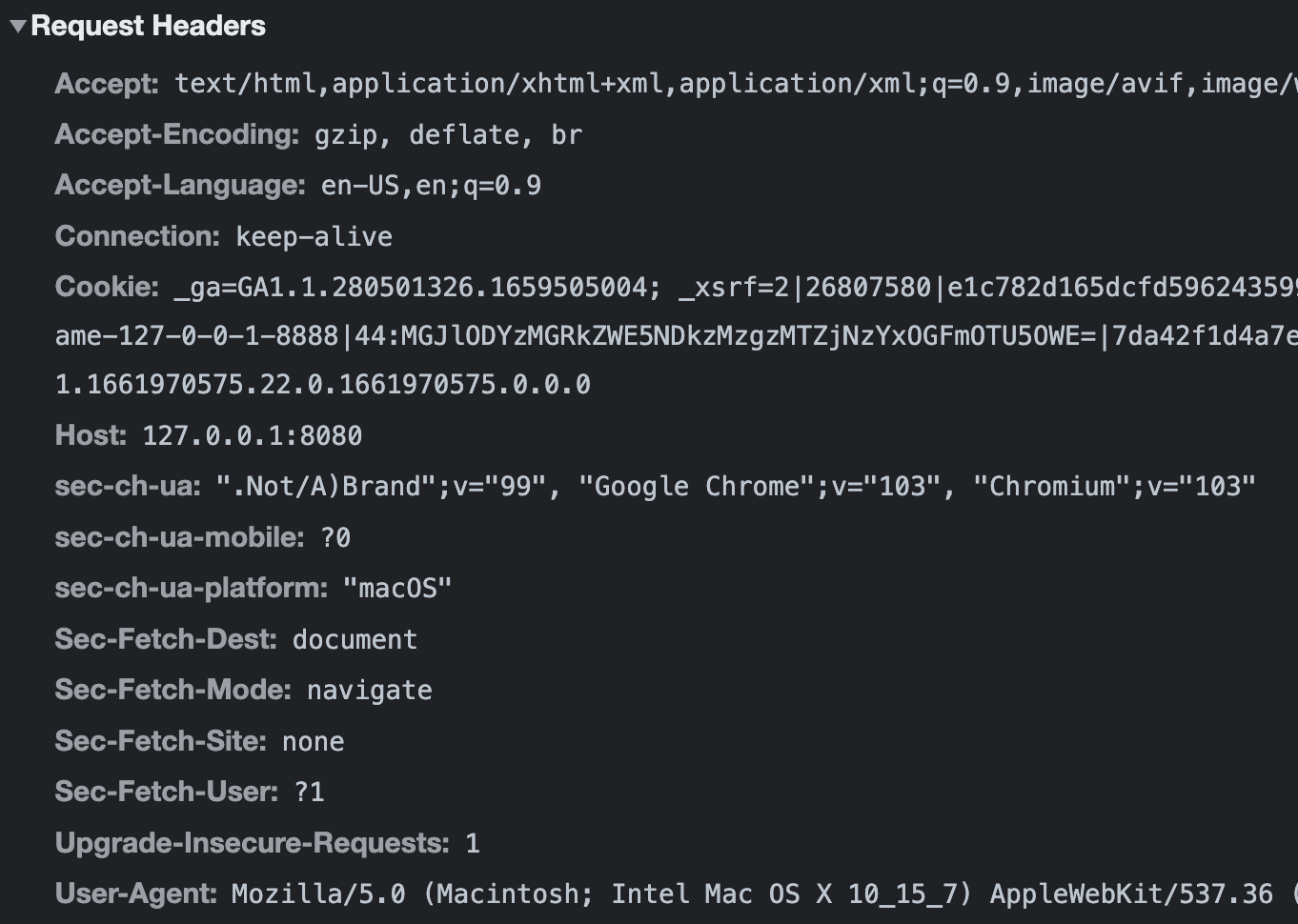

As an example, here is a set of request headers generated using Chrome:

Host: 127.0.0.1:8080

Connection: keep-alive

Sec-Ch-Ua: ".Not/A)Brand";v="99", "Google Chrome";v="103", "Chromium";v="103"

Sec-Ch-Ua-Mobile: ?0

Sec-Ch-Ua-Platform: "macOS"

Upgrade-Insecure-Requests: 1

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10_15_7) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/103.0.0.0 Safari/537.36

Accept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,image/avif,image/webp,image/apng,*/*;q=0.8,application/signed-exchange;v=b3;q=0.9

Sec-Fetch-Site: none

Sec-Fetch-Mode: navigate

Sec-Fetch-User: ?1

Sec-Fetch-Dest: document

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate, br

Accept-Language: en-US,en;q=0.9

Cookie: (truncated)This is what we get with Firefox, on the same computer:

Host: 127.0.0.1:8080

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10.15; rv:104.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/104.0

Accept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,image/avif,image/webp,*/*;q=0.8

Accept-Language: en-GB,en;q=0.5

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate, br

Connection: keep-alive

Cookie: (truncated)

Upgrade-Insecure-Requests: 1

Sec-Fetch-Dest: document

Sec-Fetch-Mode: navigate

Sec-Fetch-Site: none

Sec-Fetch-User: ?1Safari, on the other hand, is much more minimalistic:

Host: 127.0.0.1:8080

Upgrade-Insecure-Requests: 1

Accept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,*/*;q=0.8

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10_15_7) AppleWebKit/605.1.15 (KHTML, like Gecko) Version/15.6 Safari/605.1.15

Accept-Language: en-GB,en;q=0.9

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate

Connection: keep-aliveNote that to ascertain the header order reliably, you should consider only the actual HTTP requests sent by the browser. Chrome DevTools, for example, shows headers in alphabetical order (compare this with the actual header order above!):

Here are some good articles on HTTP header fingerprinting:

Application-level dimensions

Depending on the context, application logs enable additional dimensions such as:

- Username and e-mail address: This can be quite insightful, as it is chosen by the user. In particular, an e-mail address username@domain.com provides both a username and a domain. That said, remember that a user's identity is not verified until a successful login -- and even a successful login might not necessarily confirm that a user is who he or she claims to be. So tread carefully when using this as a dimension! One application of using username and e-mail address as a dimension is that it is easy to compare sessions (or "user journeys") across time and look for anomalies.

- Phone number

- Zip code or other address information

- Credit card numbers: Given the sensitivity of credit card numbers, one alternative is to use a masked credit card number comprising the first six digits (BIN) and last four digits.

- Browser fingerprints: There are numerous browser "fingerprints" that can be constructed. (I use "fingerprints" in quotes because none of them are truly as unique as a fingerprint.) Typically, these are constructed based on certain browser and device properties that provide some entropy. Examples of properties include screen resolution, the browser's WebGL renderer, fonts supported by the browser, and the browser's semi-unique media device ID.

- Device-specific identifiers: This is the native app equivalent of browser fingerprints. For example, the IDFV in iOS, or Android ID and Advertising ID on Android. These are useful dimensions as they tend to provide some amount of stability over time, especially for a short period of time. Note that some of these are application-specific and not device-specific. Apple and Google are constantly fine-tuning the availability of such IDs. Today, Apple and Google both restrict access to the most specific (and persistent) identifiers, such as the phone's IMEI number and actual MAC address.

- Residual data: This works similarly to a cookie, making it mostly immune to collision, but the unique identifier is saved in something like the browser's local storage instead. This value is typically seen only as part of a POST request payload, and the user needs to enable Javascript. (The absence of such an identifier is therefore also meaningful because virtually all users would keep Javascript enabled.)

Considerations around dimensions

Dimension entropy

When working with dimensions, there is a balance between collision and division. Smaller dimensions such as IP addresses are vulnerable to division, which means that the same "logical group" of traffic may be associated with multiple dimension values. Case in point: If a (paranoid) user diligently deletes cookies after every browsing session, the user will have a new cookie for each session. The cookie would therefore not be a very useful dimension to track this user. Larger dimensions such as UA are of course vulnerable to collision. However, this also means that unusual dimension values (such as an uncommon UA string or an obscure out-of-country ASN) will still stand out more.

Dimension durability

When aggregating traffic around dimensions, it is important to consider how long each dimension is likely to be valid. Usernames and cookie values tend to be the most long-lived, while IP address tends to be rather ephemeral.

Spoofing dimension values

Some dimension values, particularly those reported in the HTTP header, can be easily spoofed. Attackers do this to their advantage to "blend in with the crowd." Application-level dimensions are much harder to spoof, especially if the right precautions are taken to ensure the integrity of those values.

A good example is the user agent. This is specified in the header, and it can also be retrieved within the browser with some Javascript: navigation.userAgent. Suppose that you are using Chrome and are trying to pretend to be Firefox -- It would be possible to identify that you are lying about your browser because you are not sending headers in the right order, computing floating point math differently, or even rendering emojis differently.

Tell-tale signs of legitimate human traffic

To identify bot traffic, we first have to understand the characteristics of good human traffic. For the most popular values of each dimension, there are some "typical" characteristics.

Diurnal traffic

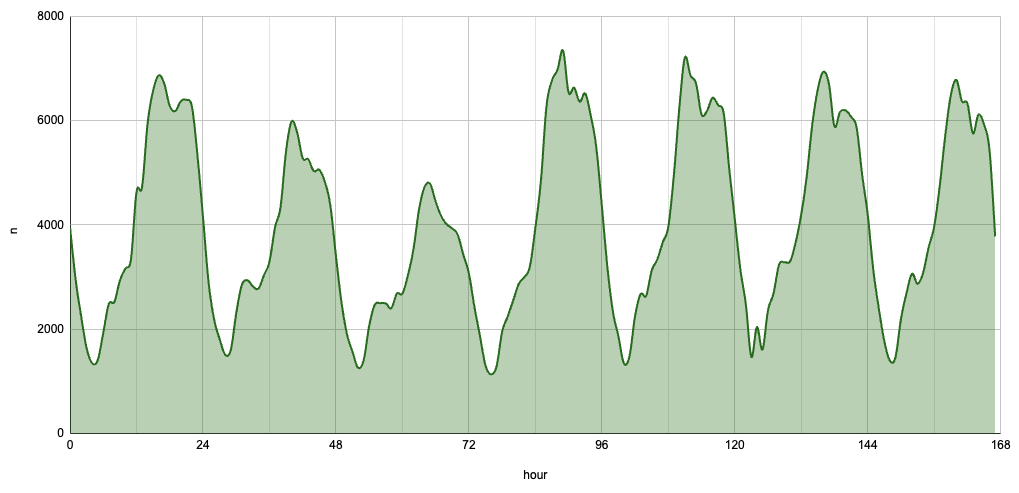

Human traffic is almost always diurnal, because people tend to sleep at night. Every dimension with sufficient traffic should appear diurnal, if it is legitimate human traffic.

You can describe the "diurnality" of some traffic in various ways.

If you consider the traffic shape to be a wave, then you can describe it by its periodicity (or frequency - which is the inverse) and amplitude. Empirically, you could generate a time series (e.g. volume per hour) and perform a Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) to estimate its principal frequency. For perfectly diurnal traffic, this frequency will be 24 hours. Here is a useful article that shows how to perform an FFT on time series data using NumPy.

Traffic on weekends also tends to be lower than traffic on weekdays. (However, this is not always true -- There are some applications that buck this trend.) Can you spot the two days that constitute a weekend in the traffic chart above?

The amplitude of a wave is typically described by the ratio of the wave's peak to its equilibrium. However, "equilibrium" does not make too much sense in web traffic -- You could describe it as the mean, but given that a time series of the traffic would represent potentially multiple periodicities, One way would be to consider the ratio of the mean peak traffic volume to the mean trough traffic volume. For example, in the above chart, the mean peak traffic volume is around 7,000 requests per hour, and the mean trough volume is around 1,500 requests per hour -- This makes for a ratio of ~4.7.

Generally, the stronger the diurnal pattern, the more likely that the (human) users are from a single time zone. With users from multiple time zones, especially time zones that are far apart, the ratio of peak to trough volume will be much lower – at any time of the day, there are always a significant number of users who are not sleeping!

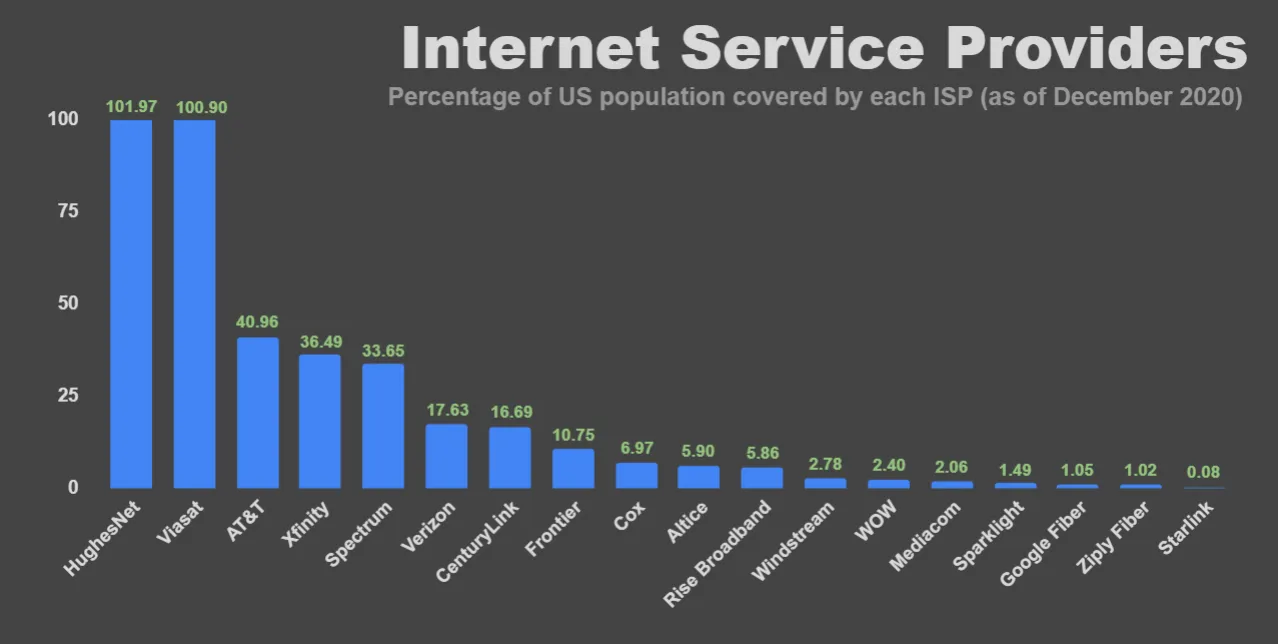

Residential and mobile ASNs

Most legitimate human traffic would also be from residential or mobile ASNs. This is difficult to infer from just looking at IP addresses, so it is useful to enrich traffic logs with ASN data. For example, the top ISPs in the U.S. include AT&T, Xfinity, Spectrum, Verizon, Centurylink, Frontier, Cox, Windstream, WOW, and Mediacom. There are also a number of small satellite internet providers that cover most addresses in the U.S., including HughesNet and Viasat.

Of course, this does not mean that every user from one of these ISPs is legitimate. But if you see a large volume of traffic from one of these ISPs, and there are no unusual characteristics on the aggregate, it is relatively safe to assume that those will be human users.

The distribution of legitimate ASNs will generally follow a power law distribution. (So does the distribution of user agent strings.)

One would also expect a website's traffic to originate from countries where the website's users are located. For example, an e-commerce site selling only to the U.S. market should not expect to receive significant traffic from Africa!

Note that residential ASNs may not enjoy the same reputation in some countries. For example, Globe Telecom, the largest consumer internet provider in the Philippines, is also a significant originator of bot traffic.

Login success rate

If you have access to application logs, such as those pertaining to logins, a good indicator of legitimate human traffic is a "reasonable" login success rate.

What is "reasonable"? Typically, something that is 60% to 90% is quite likely, for a consumer web application. One would not expect users to log in successfully only <20% of the time, or >99% of the time. Humans make typos and misremember their passwords, while bots usually don't.

Number of accounts accessed

A single device should typically not access a large number of accounts. By using dimensions that closely approximate devices, such as cookie values or browser/device fingerprints, we can explore the distribution of the number of accounts accessed by each device, and identify outliers.

Depending on the type of website in question, there may be some exceptions to this. For example, a bank might operate a digital kiosk where users can access their accounts – these kiosks (and their IP addresses, fingerprints, etc) would be associated with a large number of accounts accessed.

Tell-tale signs of bot traffic

Now that we know what good traffic looks like, let us consider some tell-tale signs of bot traffic. Note that these signs generally apply regardless of whether the bots are malicious or not. It is usually possible to understand a bot's intent only by looking at aggregate bot traffic.

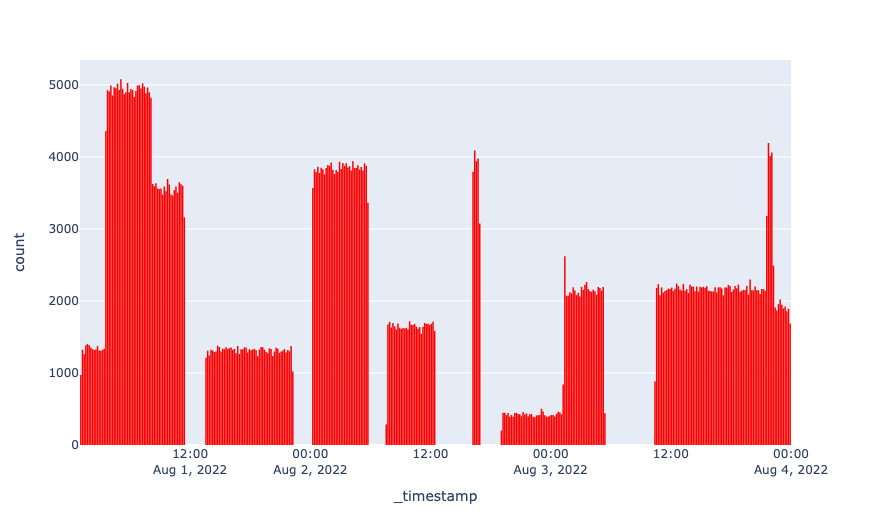

Spiky traffic

Since organic traffic is likely to follow a diurnal pattern, any significant spikes in traffic are anomalous. The chart above shows a plot of traffic that is artificially generated -- This is essentially the same pattern of traffic as a major bot attack on a website.

Let V(t) be the volume of traffic at time t. A spike can be defined as some V(t), such that V(t) / V(t-n) > m and V(t+n) > m, where n is relatively small and m is relatively large. Consider the spike at around 5 pm on August 2nd in the chart above. The spike is relatively short-lived, and traffic scales up from zero to almost 4,000 transactions per ten minutes, and down to zero again. This is possible only with a script.

Low entropy traffic

Low entropy traffic is visible as a very "flat" traffic volume across a significant amount of time, e.g. dV(t)/dt ~= 0 for some sufficiently large range of t. This is very difficult to accomplish for any substantially large group of legitimate traffic. Another approach is to consider the time interval between sequential transactions from the same dimension. Typically, these interarrival timings are exponentially distributed. Bots would usually send traffic very consistently, and so the interarrival timings of bot traffic tend to be uniformly distributed. Theoretically, you can calculate the interarrival timings of transactions for every sufficiently large dimension, and mathematically check if such timings are closer to an exponential or uniform distribution. This would be quite computationally intensive, though!

In addition to having low entropy across time, less sophisticated bots also tend to have low entropy across IP addresses, ASNs, UAs, and other areas. As mentioned, ASNs and UAs typically follow a power law distribution. This is consistent with the "80-20" rule: 80% of legitimate traffic will be from a handful of ASNs and UAs, while 20% will be from all other ASNs and UAs.

Since it is difficult for bots to commandeer a large number of IP addresses across multiple ASNs, many bots tend to use multiple IPs in a "round robin" fashion. This means that for a given selection of traffic, the variance of traffic volume across IP addresses is extremely low.

UAs tend to be easier to spoof. That said, it is still quite rare for an attacker to send traffic that correctly mimics the power law UA distribution of legitimate traffic.

Low-quality ASNs and IPs

This is fairly straightforward. If a significant portion of any traffic (aggregated by some dimension) originated from low-quality ASNs, the traffic is more likely to be automated.

Low-quality ASNs would generally include cloud and hosting ASNs. Legitimate humans would generally not use these ASNs (unless they are using a VPN), and so it is likely that most traffic from such ASNs would be bots.

Some relatively "popular" ASNs for bots are EGI Hosting, Linode, Joe's Datacenter, Server Mania, and Quadranet. With sufficient (i.e., a huge amount of) traffic, it would be possible to score each ASN in terms of bot and fraud risk. There are also free "bad ASN lists" online, but use them at your own risk!

IPs are more difficult to work with, as there are so many of them. Most IPs are also rather ephemeral, and an IP used maliciously today could be reassigned to a good user tomorrow. Despite this, it is possible to crawl the web for publicly available lists of IPs that are proxies, such as https://geonode.com/free-proxy-list/ and https://www.freeproxylists.net/. That said, there are (paid) commercial services that provide IP reputation scoring. One example is IPQS -- Here is a sample lookup for 204.27.60.211, which belongs to Joe's Datacenter.

Unusual user agent strings

Can you spot what is wrong with this user agent?

Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/105.0.0 Safari/537.36Answer

The Chrome version number is incorrect. The UA string states "Chrome/105.0.0", but this is invalid because Chromium version numbers should comprise four parts: MAJOR.MINOR.BUILD.PATCH -- e.g. 105.0.5195.102 would be a valid version.

It is difficult to identify anomalies in UA strings. There are a huge number of UA strings in circulation, and it is impossible to be 100% certain whether a particular UA string is valid.

That said, given that UA strings follow a power law distribution, it's possible to assess the validity of most UA strings with a little effort. According to Similarweb, the two most popular browsers across desktop and mobile are Chrome (62%) and Safari (24%). These constitute ~86% of all browser traffic! There are a finite number of releases for each browser, and theoretically, it should be straightforward to identify whether a self-proclaimed Chrome or Safari browser is using a valid UA string.

Some UA strings are clearly generated by scripts, and some are clearly malicious. Here are some recent examples:

UA string | Comments |

|---|---|

| Someone probably copied this from a list and used it without an awareness of what UA strings actually look like. |

| Self-declared headless Chrome, what more could you ask for? |

| Look at the quotes! |

This is an empty string. | |

| This looks like a Python tuple, with a proper UA string as the first element of the tuple. |

| Someone might have mixed up the IP address and UA headers. |

| This is a literal "NULL" value! |

| Scanners often inject code into headers, to identify potential code injection vulnerabilities. This looks like a Linux command. |

| More code injection. |

In addition to unusual UA strings, it is also worth looking out for traffic originating from Linux. Such traffic usually contains (X11; Linux x86_64) within the UA string. While there are many (legitimate!) Linux users, it is a fact that most users do not surf the web on Linux systems.

Member discussion