Browser-based signals

How can we spot potentially inauthentic browsers and users?

The browser is a rich source of data about the user. From the browser, we can collect signals that tell us many useful things, such as:

- Whether the browser environment is authentic or spoofed (such as being controlled by a script)

- Whether the browser is lying about its identity or its capabilities

- What kind of system and hardware the browser is running on

- Where in the world the user might be located

- Whether we have seen the particular browser before

- The user's behavior

It will take a book to cover all of the useful signals that can be derived from the browser. In this article, we will focus on a small subset of signals that capture the user's behavior.

User interaction

Using Javascript, we are able to capture the many aspects in which users interact with the browser. Here are four main aspects.

Mouse events

The most common mouse event is a mouse move. By polling the current mouse coordinates at a specified frequency (say 50ms), we can paint a picture of how the user is moving the mouse. Coordinates are typically referenced with the top left of the document being (0, 0), although it is possible to obtain coordinates relative to other origins, too, such as a particular page element.

We can also capture mouse clicks. Each mouse click actually comprises mouse down and mouse up events – For example, if you hold down your mouse button and do not let it go, only a mouse down event will be triggered (and no mouse up or mouse click). This often occurs when a user drags the mouse across the webpage, such as while selecting text. The mouse click is usually triggered at the same time as a mouse up.

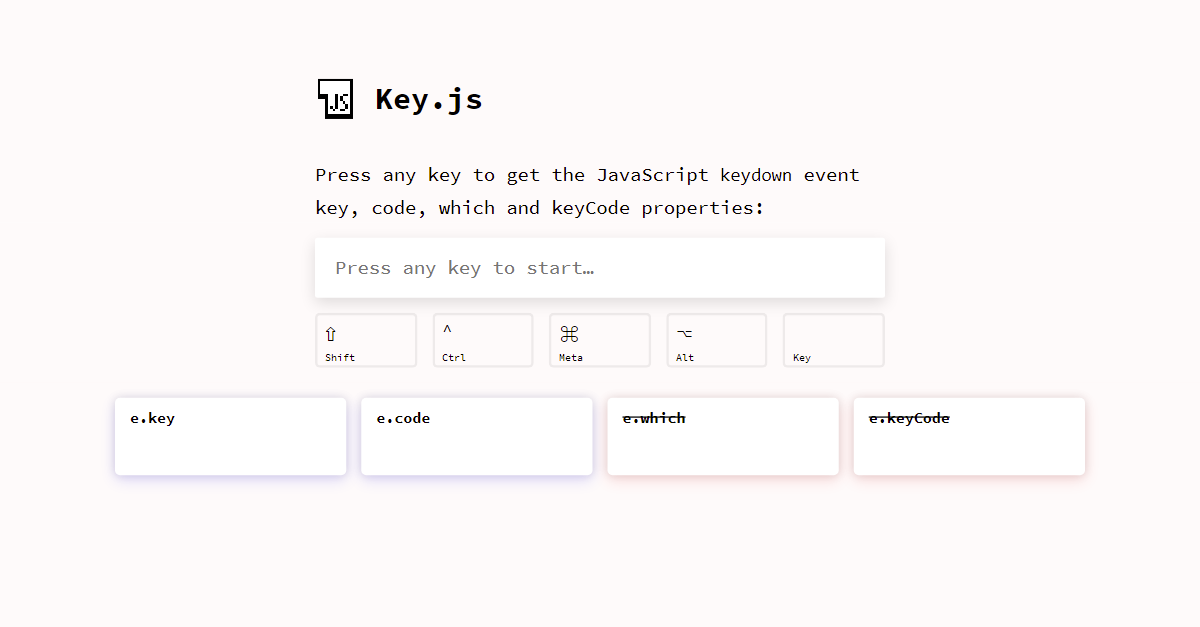

Keyboard events

Similarly, every key press is preceded by a key down event – Key press events generally occur at the same time as the key up event. This often happens when a user holds down a key, such as Shift, or Control/command. For example, when pasting something into a website, a user will often trigger Command + V, with the timestamp of "Command" typically coming slightly earlier than the "V". Developers can also capture the specific key that is triggered – Each key is assigned a unique integer based generally on its ASCII keycode. However, it is typically a wise decision to mask all printable characters to preserve end users' privacy.

You can try this out here:

Screen and browser dimensions

We can infer a great deal about the user and how the user is interacting with the browser by collecting signals about the user's screen resolution and browser size.

Historically, this has been a rather confusing exercise, as the browser makes available numerous properties pertaining to screen and browser dimensions and offsets that are closely related but ultimately different. This confusion, however, is valuable for us because we can develop a good understanding of how the page is represented within the browser.

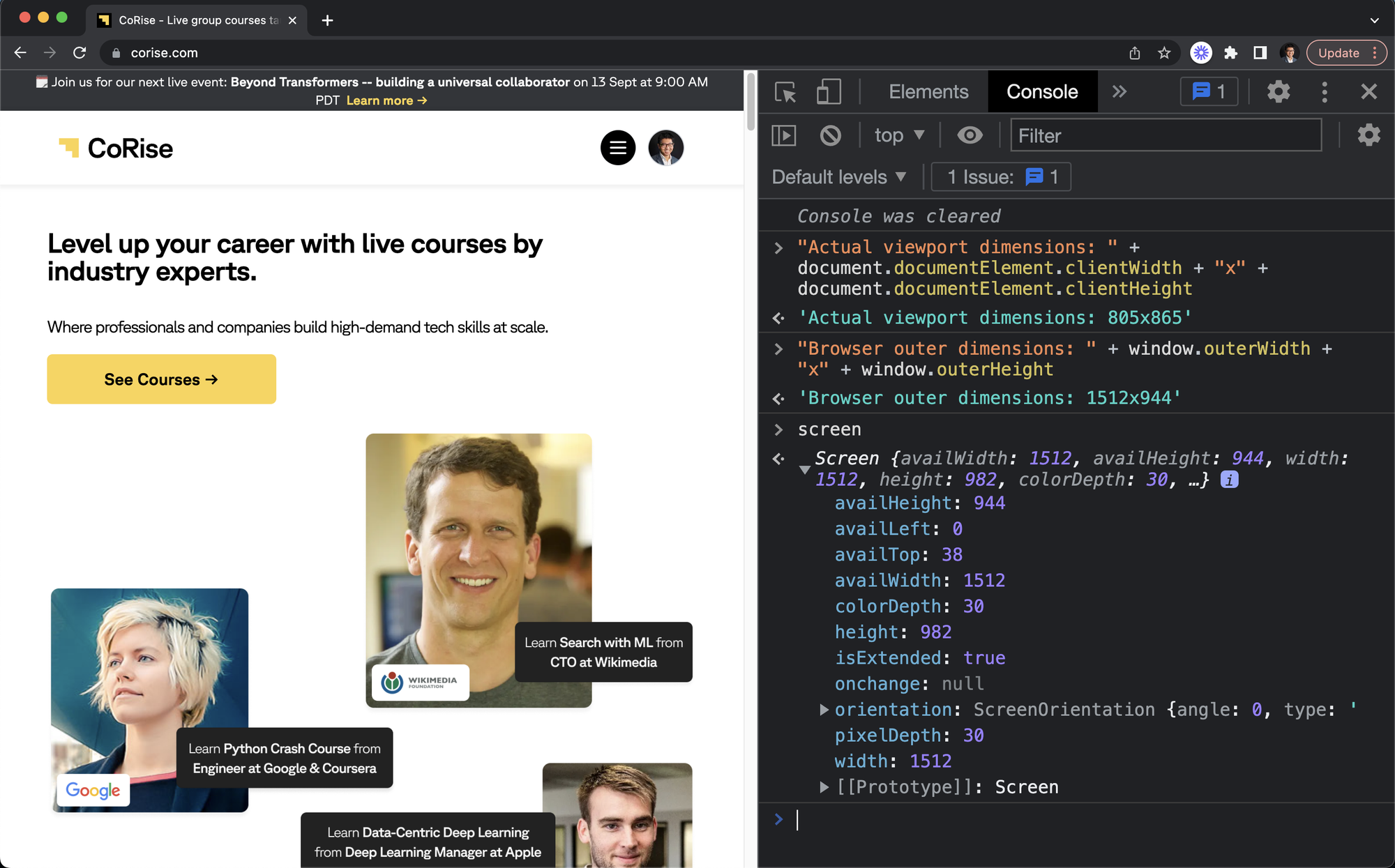

If you are viewing this article within a desktop/laptop browser window (i.e., not your phone or tablet!), you can view a lot directly within your browser's developer tools.

Simply right-click this page and click "Inspect", or press F12 or Cmd+Option+I on Mac (or Ctrl+Shift+I on Windows).

In the console, type screen and run it. You will see something like:

availHeight: 944

availLeft: 0

availTop: 38

availWidth: 1512

colorDepth: 30

height: 982

isExtended: true

onchange: null

orientation: ScreenOrientation

angle: 0

onchange: null

type: "landscape-primary"

[[Prototype]]: ScreenOrientation

pixelDepth: 30

width: 1512Now, your developer tools are probably docked on the right-hand side of your browser window, like this:

Try running these two commands in the console:

"Actual viewport dimensions: " + document.documentElement.clientWidth + "x" + document.documentElement.clientHeight

"Browser outer dimensions: " + window.outerWidth + "x" + window.outerHeight

You will see that there is a significant discrepancy between the browser's overall width (window.outerWidth) and the actual "page" width (i.e. viewport width, document.documentElement.clientWidth).

With our data science hats on, we can create a feature to detect whether developer tools are open by checking if the viewport width and overall width differ by more than a certain threshold, say 250px.

Other useful browser signals

Many other signals can be found within the browser. Many of these come from the Navigator API (accessed via window.navigator), which represents the state and identity of the browser. I have put together a sample below to provide an idea of the diversity of these signals:

| Property(navigator.* unless otherwise specified) | Sample Value | What does it tell us? |

|---|---|---|

language |

en-GB |

The primary language used in the user's OS. Gives a clue as to where the user is from. |

cookieEnabled |

true |

Whether cookies are enabled. Note that this is true even for incognito mode -- The browser just maintains a separate cookie space. |

maxTouchPoints |

0 |

Whether the device has a touchscreen. I am writing this on a MacbookPro, so unfortunately this is zero! |

hardwareConcurrency |

8 |

The number of logical CPU cores available to the browser. |

bluetooth.getAvailability() |

false |

Whether Bluetooth is enabled. This is not supported on Firefox. |

webdriver |

true |

Whether the browser is controlled by automation or used headlessly. No self-respecting bot will allow this to be reported as true (there are ways to spoof this), but if you do spot a browser reporting it as such, you can be pretty sure that it's automation! |

window.history.length |

7 |

The number of entries in the browser's history. Note that this typically maxes out at some pretty large number, such as 50. The browser won't report anything beyond that. |

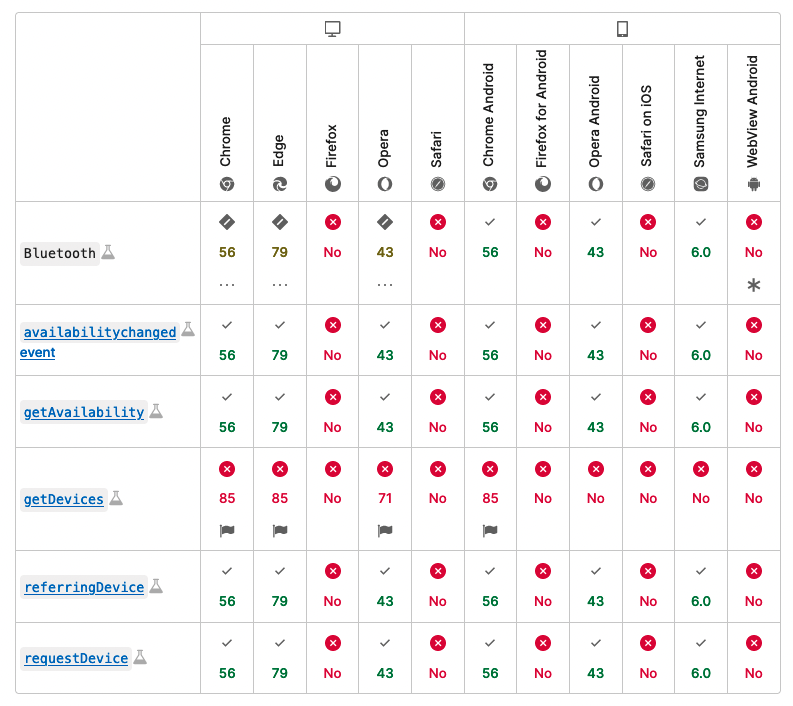

Signal availability

Note that many of the above properties are not supported across all browsers. For example, the Bluetooth API is supported on Chrome, Edge, and Opera, but not on Firefox or Safari. Support for various properties is generally patchy:

We can actually use this patchy support to our advantage, to identify browsers. For example, if you run the command window.bluetooth == null in Chrome and Firefox, it will return true for Firefox and false for Chrome.

Tests like this are most helpful when compared with other forms of self-identification provided by the browser. Let's say you get false for the above command, and yet the browser UA string is reported as Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10.15; rv:104.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/104.0 (i.e., Firefox). You'll be able to recognize this discrepancy! If the browser is lying about this, the browser (and the user!) could well be lying about other things as well.

Signal integrity and evading detection

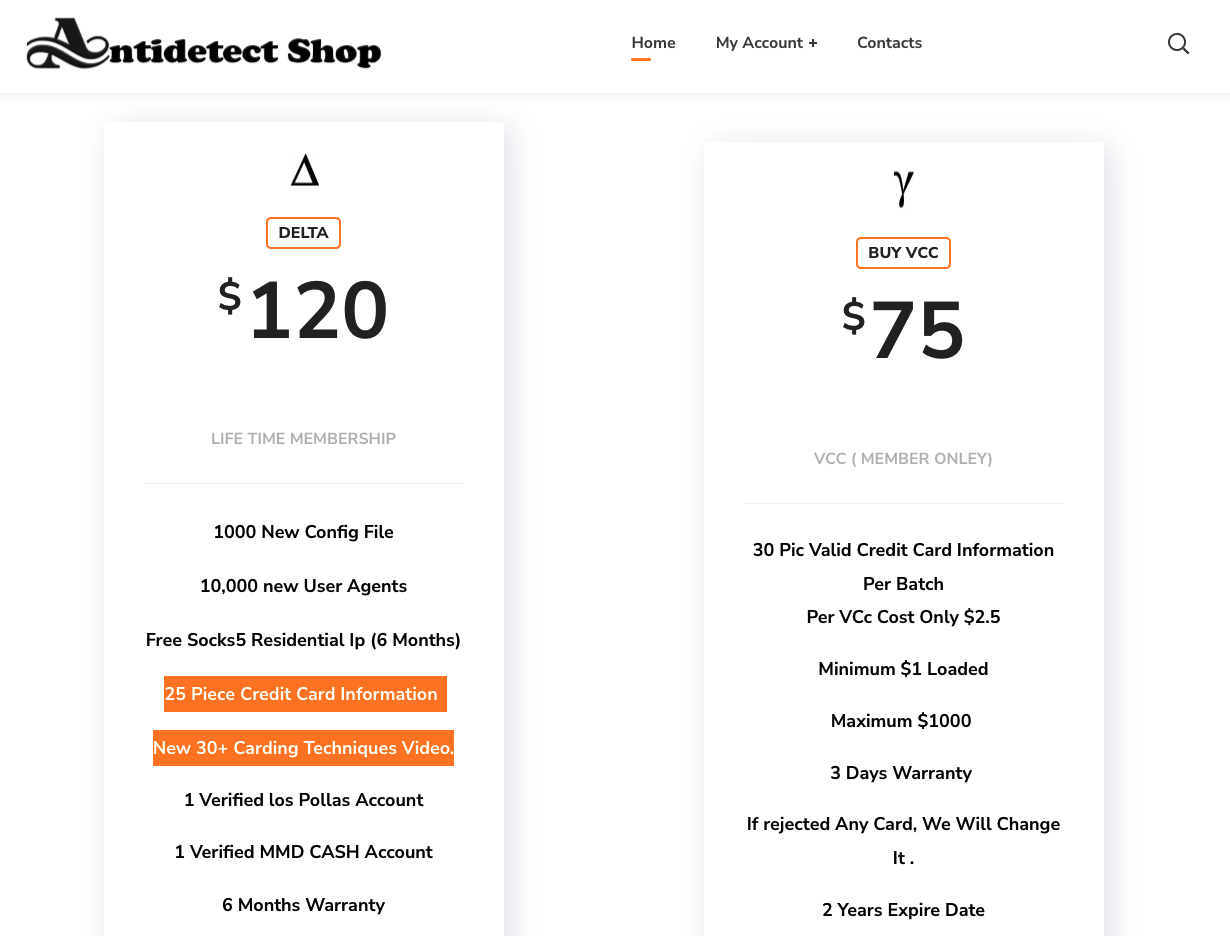

It is also important to note that there is no guarantee that any of the screen, navigator, or other properties will return authentic values. There will always exist the possibility that some values will be spoofed. It is in fact fairly trivial to download browser extensions and special browsers designed specifically to evade detection. Just google "antidetect browser".

Such "antidetect browsers" have matured significantly over the years, and are popular with fraudsters.

These browsers are highly customizable, and overwhelmingly offer easy support for custom proxies and VPNs. Some browsers are even bundled with stolen credit cards and carding tutorials!

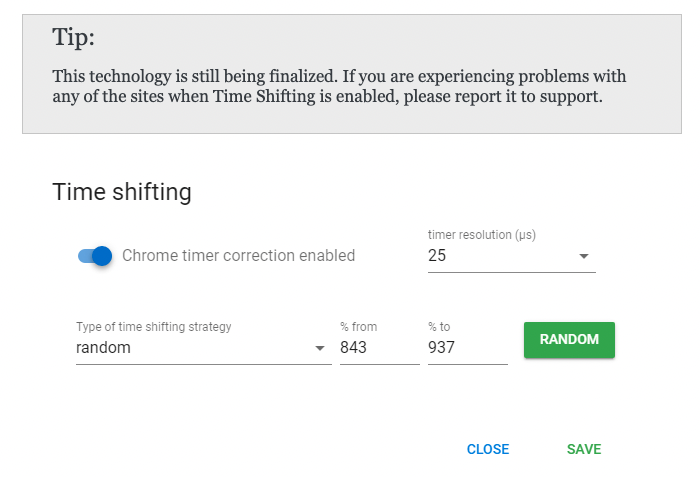

Another innovative browser offers a feature called "time shifting", which allows you to adjust Chrome's internal clock so that your actions on a website (mouse movements and keystrokes, primarily) appear different each time. This makes it harder for websites to track your user behavior and profile your identity.

The best way to combat such spoofed browser environments is to track the user's actions over time. What the user does cannot be spoofed, even if how the user does something is unreliable. It is also still worth it to collect various browser signals, even if the values are spoofed – It is not trivial for a browser to spoof every single value correctly and in tandem. Look out for potential inconsistencies everywhere.

Member discussion